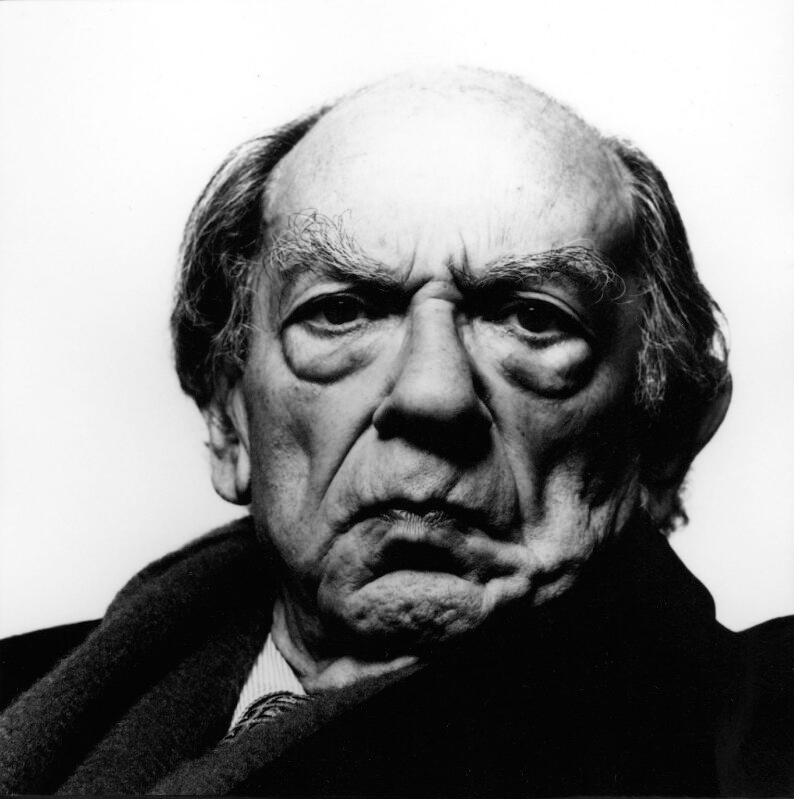

Sir Isaiah Berlin invited me to tea in Piccadilly sometime in August 1995, at the height of the 1995 heatwave. The hottest sunshine since 1659 baked London, otherwise teased by a faint breeze. We had met by chance at a late-night Stravinsky prom at the Albert Hall. The 10pm concerts, without an interval, are more intimate occasions than the main events of early evening and the programming more esoteric. We recognized each other in the uncrowded front foyer (before the 2014 makeover that installed a glass cube to the fore). Fifteen years earlier I had finally left Wolfson College Oxford where, when I began in 1974, Isaiah was its first President. It wasn’t a strong personal bond. But we had a love of Russian literature in common, and now, as was plain, a love of Russian music. Late liturgical compositions by Stravinsky drew us to West London on that balmy almost white night. ‘Otche nash’, ‘Bogoroditse devo’ and ‘Simvol’ Veri’– meaning ‘Our Father’ and ‘Virgin born of God’, and the ‘Symbol of Faith’ — were being performed for the first time at the Proms, with the BBC Symphony orchestra playing under Oliver Knussen and the BBC Singers conducted by Stephen Jackson. The first two pieces had Church Slavonic titles. Londoners had heard performances of The Requiem Canticles, in part a setting of the Catholic Requiem Mass, only three times since their composition in 1966. Isaiah had met Igor Fedorovich after being overwhelmed by a performance of The Rite of Spring and Oedipus Rex in Venice, and writing him a fan letter. That had been in September 1958, nearly forty years ago. He didn’t tell me at the time. He was never self-important.

The café was a stone’s throw from Albany, the exclusive eighteenth-century apartment block where Isaiah had a flat. I arrived by tube from south London, at 43 exactly half his age and a great deal poorer. My situation, and the appearance that reflected it, must have struck him, for he asked me what seemed at the time an unfathomable question, whether I knew what the rich did in their spare time. Played golf was the answer. And the women, after a visit to the couturier? I wondered. But we settled, over tomato juice for him (he’d been lunching elsewhere) and Earl Grey for me, into things Russian. I’d spent six weeks travelling down the river Volga in 1993. He’d gone back to St Petersburg and Moscow in 1988 and found the students ‘just the same’, meaning he could still feel the legacy of high-minded seriousness and social concern and love of art that inspired his beloved ‘Russian thinkers’ of 1838-48. His love was greater than mine and he upbraided me for calling Russia ‘incorrigible.’ ‘In what would you correct them?’ ‘The absence of reason in their philosophical tradition.’ His answer suggested I was barking up the wrong tree. But I answered that surely a modern people without a rational tradition lacked something essential. I quoted the thinker Berdyaev: ‘our intelligentsia don’t distinguish between true and false.’ I suggested that perhaps in the Soviet era the great faith in science had tried to make up the deficit though with grotesque results (like a reluctance for ideological reasons to accept the Theory of Relativity).

The conversation struggled a bit, but it nose-dived when I mentioned someone else I’d had tea with recently, the philosopher Roger Scruton.

I knew Roger better than Isaiah because I’d seen him at home, in his beloved Wiltshire countryside, and with his horses. He was hospitable and never condescending. We talked German philosophy and galloped through a few fields. ‘Scruton’ had saluted Isaiah’s eightieth birthday back in 1989 with a tightly argued, rather fierce piece in The Times on June 3. Did I know the essay, Isaiah asked in a tremulous voice. It was six years on and the insult might have been delivered yesterday.

I’ve since tried to make sense of the clash for myself. Roger hated liberals, that is to say, as he saw them, now wishy-washy, now ferociously ideological left-wingers of various stripes, Guardian-readers and, as he put it in The Times piece, ‘second-rate bigots who had advanced through the academic world during Isaiah’s’ reign over it.’ Phew. On a more abstract level he detested the legacy of the Enlightenment, which he felt Isaiah instantiated. For the country’s leading conservative philosopher, which Roger certainly was, the idea that universal reason promised liberty and equality was a trick. As he wrote in his piece, Enlightenment ideas ‘were useful instruments of tyranny’ whose potential was recognized by none other than Marx. Berlin had written a life and work failing to condemn Marx.

But the charge was ridiculous. Here was an eminent philosopher and a great imaginative thinker squandering his mind on relentless ideological warfare. Did no one tell him Isaiah was never a hero of the political Left in Britain?

Then again that wasn’t the real sting of the piece. The philosopher and editor Henry Hardy, in his reminiscence of a fifty-year friendship, My Life with Isaiah Berlin, thinks it was the sentence which read:

‘I sense a dearth of those experiences in which the suspicion of the liberal idea is rooted: experiences of the sacred and the erotic, of mourning and holy dread’ that really hit home. If Hardy is right, what was the 80-year-old Isaiah Berlin to think when he read that indictment of his career? That his love life hadn’t been sufficiently Wagnerian? In fact it was not only an absurd accusation but an error of judgement.

Of course Scruton couldn’t know what Berlin had written to Stravinsky back in 1958. I couldn’t have imagined it either, so I was delighted to come across it in the Letters.

‘I thought the Sacre [du Printemps] and Oedipus [Rex] glowed…something so firm, so splendid, so marvellously made and untouchable by change in fashion and feeling, can still dominate everybody and everything, and stand up, and remain beautiful and elusively strong and faultless, in the crumbling of so much else…’

Nor could Roger know what I intuited that sultry August of 1995, when Isaiah had only two more years to live: that he was at that concert of Stravinsky’s music for the Orthodox rite because he was reverting to what was closest to his heart.

Still there’s no doubt in my mind: Roger Scruton was unfair to Isaiah Berlin. He willfully ignored what Berlin wrote in admiration of the ‘Counter-Enlightenment’ — a term he even helped to popularize anew. Roger might not have known of Isaiah’s late-confessed love of the Russian mystical philosopher Lev Shestov, but the essays on Herder and Hamann and Vico were long established. The non-rationalists Isaiah admired were definitely not forebears of Marx. They were closer to the German Romantics, thinkers much more in tune ‘sacred…and holy dread’. Roger, I suspect, often sacrificed the subtleties he perceived in life as it was lived in order to score an ideological victory on the page.

I admired them both. They had a formidable knowledge and love of music and both had the un-English habit of living by ideas. At the heart of our interests lay the great aesthetic-minded Germans of the eighteenth century, Goethe and Schiller and Kant, who in their turn had tutored the Russian Idealists of the Marvellous Decade (the topic of one of Isaiah’s most famous essays). I had gone to Oxford in the mid-1970s to write a thesis on that cross-influence and shared it with Isaiah. In the 1990s I was back reading the Germans, quoting them to Roger. He often paraphrased their insights, wishing no doubt that they had been English. It was not for nothing that it was as Professor of Aesthetics at Birkbeck College that he signed his anti-Berlin diatribe.

Which leads me to another underlying drama of that day, framed by my edgy relations with two great minds, and the rare, intense dislike Isaiah Berlin felt for Roger Scruton: it was the painfulness of the English class system and its dislike for Johnny Foreigner. We were all caught up in it. Isaiah’s early anxieties as a Latvian and a Jew made him more emollient than he might otherwise have been in British society; in private he could be catty and unfriendly to the efforts of fellow Jews. He hated the German Jewish philosophers whom Hitler drove into exile, Hannah Arendt who escaped meeting him, and Theodor Adorno, whom he privately ridiculed and patronized in Oxford. He took a similarly deprecating attitude to the critic George Steiner two generations on. So Berlin anglicized himself. But there was a price to pay. As he told the musicologist Robert Craft in the wake of his billet doux to Stravinsky: ‘I had a most moving and bouleversant experience and I am too anglicized to be able to do it [write about it] simply and convincingly.’ Roger was free of these prejudices and some of the emotional self-consciousness. He liked rather to show off feelings bordering on sentimentality. But, like me the product of a grammar school, he was full of social anxieties. These he turned into barbs against the perceived left-wing intellectual establishment. Out of sheer respect I was devastated to hear him describe himself, around 1990, despite all the ambitions in which he had succeeded, as ‘of the wrong social class’. I was even outraged to read him, on behalf of his never-never conservative England, recommend that we all live according to our station (though the occasional individual might rise).

The word ‘coward’ came up in Isaiah’s alarmed response to Roger’s name. The memory is fuzzy here. I had thought Roger had called him a coward in print, but the printed text bears only the headline ‘Freedom’s cautious defender.’ Perhaps this was insult enough for Isaiah. Or was the cowardice implied the other way round? I certainly remember Isaiah saying in a sudden gossipy confidence: ‘You know when Scruton passed me in Albany he covered his face.’ (Roger too had a flat in Albany, one of the marks of belonging to the Establishment.)

‘Love to Scruton!’ Isaiah called, with a note of hysteria in his voice, as I prised my bare legs off the leatherette banquette that stifling afternoon, yanked down my flimsy summer dress and went back my Russian thinkers and my book on Nietzsche. I don’t write in reproach. I just happened to be there, on the periphery of the most intense English intellectual life, in the last decade of the twentieth century.